- Seven months after Hurricane Helene, Chimney Rock rebuilds with resilience

- Wildfire in New Jersey Pine Barrens expected to grow before it’s contained, officials say

- Storm damage forces recovery efforts in Lancaster, Chester counties

- Evacuation orders lifted as fast-moving New Jersey wildfire burns

- Heartbreak for NC resident as wildfire reduces lifetime home to ashes

NC State team studies unique tornado threat

Raleigh, N.C. — North Carolina is no stranger to tornado danger.

A quick tornado spawned from a band of storms March 31, bringing 100-mile-per-hour winds to Research Triangle Park. The storm damaged the roof of Pfizer’s office building and took down trees. No one was hurt, but the storm reminded the Triangle of the severe weather threats we face.

Most tornadoes in the United States form in isolated storms called supercells. These storms are most commonly found in the Great Plains. Researchers have studied supercells carefully over the decades, leading to a good understanding of how the storms form and what conditions lead them to spawn tornadoes.

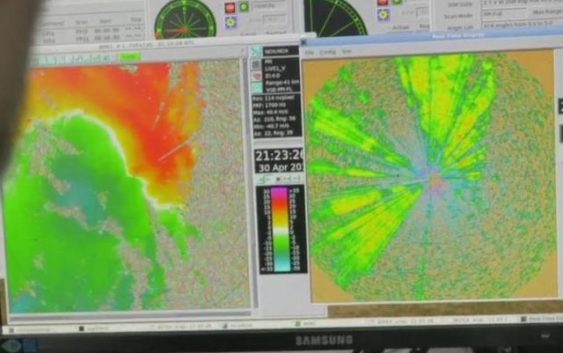

In the southeastern U.S., we are especially vulnerable to tornadoes from a different kind of thunderstorm. Quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS), also known as “squall lines,” bring a unique tornado threat. Tornadoes from these systems tend to be weaker and briefer than those formed in supercells, making them more difficult to detect on Doppler radar. These tornadoes often occur at night and during the fall and winter, when people generally are not expecting severe weather.

Those characteristics are an especially dangerous combination.

“Unfortunately, tornadoes have a higher fatality rate in the Southeast than they do in other parts of the country,” said Matthew Parker, an N.C. State University meteorology professor.

Parker is part of a team participating in one of the nation’s largest-ever severe weather field studies. It’s called PERiLS (Propagation, Evolution and Rotation in Linear Storms). A team of 14 faculty and students from N.C. State are joining colleagues from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association and eight universities to head into the Deep South and gather data as squall lines pass.

“We set up a network, and we let the squall line move through the network and catch what we can with our net,” Parker said.

Using several mobile Doppler radars, weather balloons, drones and other instruments, the teams are gathering data to make a model of the atmosphere over a few hours. They’re looking for changes in temperature, wind and humidity that can lead to tornado formation. The data hopefully will give meteorologists a better understanding of the processes that lead to tornadoes in squall line events.

“We want to improve forecasts, improve warnings and improve public awareness,” Parker said.

The PERiLS teams have deployed four times in recent weeks to gather data during severe weather events in Mississippi, Alabama and Missouri. Parker says the team already has gathered valuable data this season. Their mission will continue through the spring of 2023.